Shallow mining ponds overwhelm a former

river system in the La Pampa region of Madre de Dios, Peru.

The colors of the

ponds reflect suspended sediment and algae growth following the cessation of

gold mining.

Credit: Jason Houston (iLCP Redsecker Response Fund/CEES/CINCIA)

Gold and mineral mining

in and near rivers across the tropics is degrading waterways in 49 countries,

according to a Dartmouth-led study. Published in Nature, the findings represent

the first physical footprint of river mining and its hydrological impacts on a

global scale.

River mining often involves intensive

excavation, which results in deforestation and increased erosion. Much of the

excavated material is released to rivers, disrupting aquatic life in ecosystems

nearby and downstream. This inorganic sediment, particles of clay, silt, and

sand, is carried by rivers as "suspended sediment," transmitting the

environmental effects of mining downstream.

Prior research has reported that such

suspended sediment may also carry toxins such as mercury used in river mining

processes, which further affects water quality and can be detrimental to human

health and the environment.

"For hundreds, if not perhaps,

thousands of years, mining has been taking place in the tropics but never on

the scale like we've seen over the past two decades," says first author

Evan Dethier, an Occidental College assistant professor, who worked on the

study while he was a postdoctoral researcher at Dartmouth. Dethier has a Ph.D.

and MS in earth sciences from Dartmouth's Guarini School of Graduate and

Advanced Studies. "The degradation of rivers from gold and river mining

throughout the tropics is a global crisis."

For the first part of the study, Dethier

and fellow researchers conducted a comprehensive analysis of river mining

across the tropics from 1984 to 2021. They analyzed information from the media

and literature, mining company reports, social media, and satellite imagery

from Lands at 5 and 7 via the NASA/United States Geological Survey Landsat

program and Sentinel-2 data, and aerial images from public sources.

They recorded over 7.5 million measurements

of rivers around the world to map mining areas, and deforestation and sediment

impacts. They also identified target minerals at the mining sites.

The results show that there are approximately

400 individual mining districts in 49 countries across the tropics. More than

80% of the mining sites are located within 20 degrees of the equator in South

America, Africa, Asia, and Oceania.

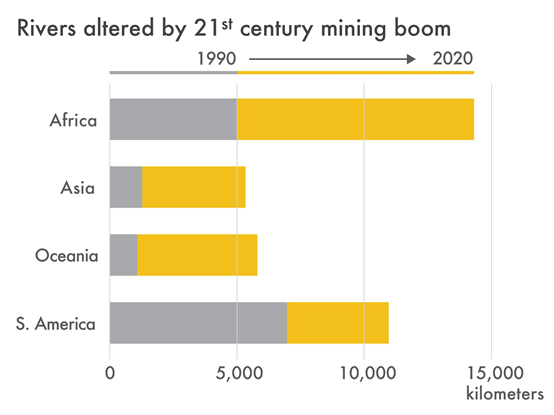

Rivers

altered by 21st century mining boom. Credit: Evan Dethier.

The team found a major uptick in mining in

the 21st century, with the emergence of mining at 60% of the sites after 2000,

and 46% after 2006, coincident with the global financial crisis. This increase

in mining continued even through the COVID-19 pandemic.

For the second part of the study, the

researchers assessed the magnitude that mining operations have had on the

amount of suspended sediment in 173 affected tropical rivers. To detect the

transport of suspended sediment using Landsat data, the team applied algorithms

that they developed during the past seven years.

The data shows that more than 35,000

kilometers of tropical rivers are affected by gold and mineral mining around

the world. Of the 500,000 kilometers of tropical rivers worldwide, about 6% of

that length is affected by such mining.

Furthermore, mining has caused suspended

sediment concentrations to double at 80% of the 173 rivers represented in the

study, relative to pre-mining levels.

"These tropical rivers go from running

clear either throughout the year or at least through part of it, to either being

choked with sediment or muddy year-round," says Dethier. "We found

that almost every single one of these mining areas had suspended sediment

transmitted downstream, on average, at least 150 to 200 kilometers (93 to 124

miles) from the mining site itself but as much as 1,200 kilometers (746 miles)

downstream."

"To give you an idea of how far the

sediment can travel downstream, this is nearly comparable to the distance from

Bangor, Maine, to Richmond, Virginia," says Dethier.

There are 30 countries that have both

active river mining operations and large tropical rivers that are more than 50

meters wide. In those countries, on average, 23% of the length of their large

rivers is affected by mining. In some countries, more than 40% of the total

length of those large rivers is altered by mining, including in French Guiana

(57%), Guyana (48%), and Cote d'Ivoire and Senegal (40%).

The study also included rivers such as the

Congo in Africa, the Irrawaddy in Asia, the Kapuas in Oceania, and the Amazon

and Magdalena in South America.

"Many of these tropical rivers systems

are very biodiverse places, if not some of the most biodiverse places on Earth

and are still currently understudied," says senior author David Lutz, a

research assistant professor of environmental studies at Dartmouth. "The

challenge here is that there are many species that could potentially become

extinguished before we even knew that they existed."

To evaluate the ecological impact of river

mining in the tropics, the team examined environmental management guidelines

used in the U.S. and elsewhere and applied the standards to their data.

Since mining began, they found that

two-thirds of the rivers represented in the study exceeded the turbidity

guidelines for protecting fish on 90% of the days or more, meaning the

cloudiness of the rivers was higher than recommended.

"When rivers and streams experience

high levels of suspended sediment, fish are unable to see their prey or

predators and their gills may become choked with sediment and damaged, which can

lead to disease or even mortality," says Lutz.

"Our team's prior work has reported on

how gold mining is a problem in the Madre de Dios region of the Peruvian

Amazon, by poisoning wildlife and people," says co-author Miles Silman,

the Andrew Sabin Family Foundation Professor of Conservation Biology, and

president of Wake Forest University's Centro de Innovación Científica Amazónica

(CINCIA).

"While gold mining has a lot of

potential to lift people out of poverty, particularly on remote tropical

frontiers, the way it is done now comes at a tremendous societal cost from

environmental degradation, mercury pollution, and corruption and criminal

networks."

While gold is the principal target for

miners and accounts for nearly 80% or more of the mining sites, mining along

rivers in central and west-central Africa, particularly, in Angola, the

Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Cameroon, makes diamonds the second most

mined mineral in the tropics. In addition, other precious minerals are also

mined. In southeast Asia, nickel is mined in Indonesia, the Philippines, and

Malaysia.

Many minerals that are used in cell phones

and electric-car batteries and are used in electronics, such as cobalt, coltan,

tungsten, and tantalite, are mined in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

"These minerals are becoming

increasingly necessary as we transition away from fossil fuels to clean

energy," says Dethier. "So, this is an important area to keep track

of."

The co-authors call on government

policymakers to work with stakeholders to help mitigate the environmental and

social impacts that mining is having on tropical rivers given that it's likely

to continue into the foreseeable future.

More information:

Evan Dethier, A global rise in alluvial

mining increases sediment load in tropical rivers, Nature (2023). DOI:

10.1038/s41586-023-06309-9. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06309-9

Details at: https://phys.org/news/2023-08-21st-century-boom-tropics-degrading.html