by Rochelle GLUZMAN

Thousands of the world's large dams are so

clogged with sediment that they risk losing more than a quarter of their

storage capacity by 2050, UN researchers said Wednesday, warning of the threat

to water security.

A new study from the UN University's

Institute for Water, Environment and Health found that, by mid-century, dams

and reservoirs will lose about 1.65 trillion cubic metres of water storage

capacity to sediment.

The figure is close to the combined annual

water use of India, China, Indonesia, France and Canada.

That is important, the researchers say,

because these big dams are a key source of hydroelectricity, flood control,

irrigation and drinking water throughout the world.

"Global water storage is going to

diminish—it is diminishing now—and that needs to be seriously taken into

account," the study's co-author and Institute director Vladimir Smakhtin

told AFP.

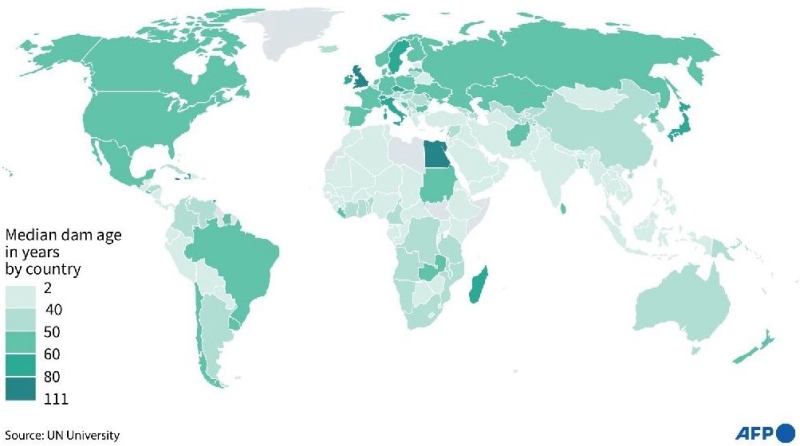

Aging dams pose safety risk

(Thousands of large dams worldwide have passed their design life of between 50 to 100 years)

Researchers looked at nearly 50,000 large

dams in 150 countries, and found that they have already lost about 16 percent

of water storage capacity.

They estimated that if build-up rates

continue at the same pace, that will increase to about 26 percent by

mid-century.

Rivers naturally wash sediment downstream

to wetlands and coasts, but dams disrupt this flow and over time the build-up

of these muddy deposits gradually reduces the space for water.

Smakhtin said this "endangers the

sustainability of future water supplies for many" as well as posing risks

to irrigation and power generation.

Part of a larger issue

Accumulation of sediment can also cause

flooding upstream and impact wildlife habitats and coastal populations

downstream.

Sedimentation is a part of a larger issue:

by 2050, tens of thousands of large dams will be near or past their intended

lifespan.

Most of the world's 60,000 big

dams—constructed between 1930 and 1970—were designed to last 50 to 100 years,

after which they risk failure, affecting more than half the global population

who will live downstream.

Large dams and reservoirs are defined as

higher than 15 metres (49 feet), or at least five metres high while holding

back no less than three million cubic metres of water.

Global warming compounds the risk in ways

that have yet to be fully measured.

"Climate change extremes like floods

and droughts will increase, and higher intensity showers are more

erosive," Smakhtin said.

This not only increases the risk of

reservoirs overflowing but also accelerates the build-up of sediment, which

affects dam safety, reduces water storage capacity and lowers energy production

in hydroelectric dams.

Alternatives

To address looming challenges of ageing

dams and reservoir sedimentation, the study authors list several measures.

Bypass, or sediment diversion, can divert

water flow downstream through a separate river channel.

Another strategy is the removal, or

"decommissioning", of a dam to re-establish the natural flow of

sediment in a river.

But addressing water storage issues is

especially complex because there is no one-size-fits-all solution, Smakhtin

said.

"The loss of water storage is

inevitable for different reasons," Smakhtin said. "So the question we

should be asking is what are the alternatives?"

A March 22-24 UN 2023 Water Conference in

New York will provide the possibility for countries to voice concerns and make

commitments for the future of water management, he said.

(Source:https://phys.org/news/2023-01-sediment-endangers.html)